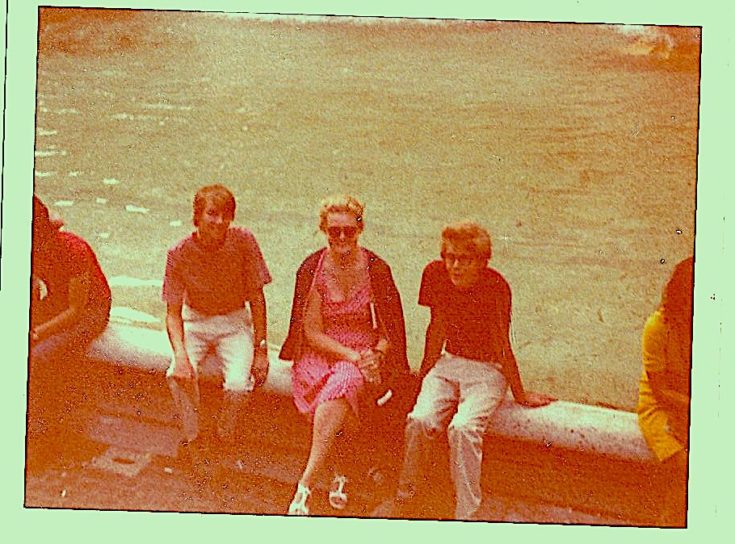

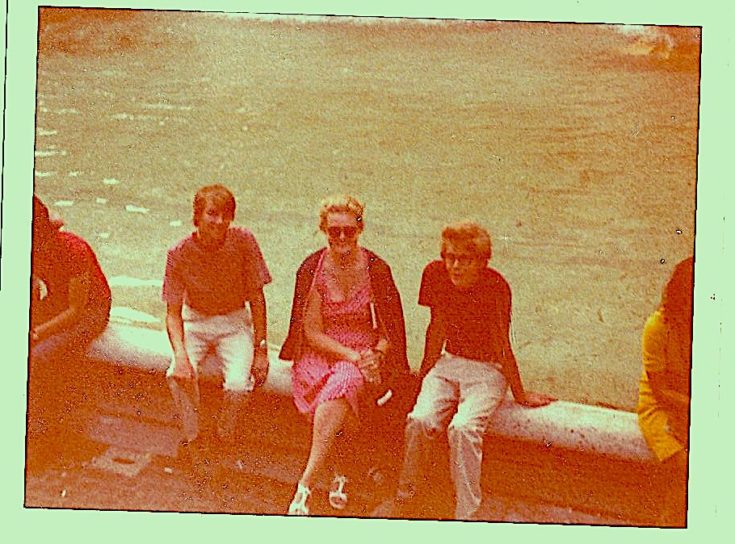

Me, my mother, and my brother John at the Trevi Fountain in Rome, 1972

My Bostonian mother, who died last Fall, was a cultural appropriator in the kitchen, and this was a good thing. Her English and Scottish ancestors had left her with only the most meager of gastronomic legacies. The totemic foods of her Boston upbringing included B & M Boston baked beans; canned brown bread, which is pretty much inedible and must be descended from some sort of sailor’s rations; frozen codfish cakes; little tins of Underwood’s Deviled Ham, a pink sandwich paste of a mysterious provenance doubtless best left unknown; and the traditional English Christmas puddings that in America are mostly only eaten in New England— but she inflected our meals with her curiosity about the world and other cultures. My father often teasingly disparaged her culinary daring, but I loved it and so did my three siblings.

Hamburger was Mom’s medium, because it was economical when she had four kids and a husband to feed. It could also quickly be conjured into a dish that dispatched us from suburban Connecticut to Cuba, China, or Italy. Sautéed with chopped onions, canned tomato sauce, sliced green cocktail olives, pimientos, and paprika, it became her version of Latin picadillo. Simmered with a small can of La Choy water chestnuts and another one of bean sprouts, plus chopped onion, celery, and soy sauce, it ferried us down the Yang-Tse to dinner. Another day, we’d have hamburger “pizza,” the meat patted into a square baking pan, topped with spaghetti sauce, a can of mushrooms, grated Romano, and oregano.

At our dinner table, we made virtual visits to Hungary with Mom’s stuffed peppers, looked forward to the Viennese rhapsody of her wiener schnitzel with an operatic flourish of fresh lemon slices and capers, and became regulars at a cozy little imaginary bistro in Paris with her Beef Burgundy, aka boeuf bourguignon, which she made with Holland House red cooking wine, a jar of onions, canned beef bouillon and a roux.

“Sometimes it would be nice to have a piece of meat that’s just a piece of meat,” my father would often say in response to a new recipe, to which she always had the same reply. “In a nation of immigrants, we get to know each other by eating each other’s foods, Sandy.”

Mom had her standards, too, once looking up from an issue of Woman’s Day to remark that pineapple alone did not make something Polynesian and another time (rightly) scoffing at recipe for clam chowder in Family Circle that rather insanely suggested you could substitute canned tuna for clams, fresh or canned.

A busy and very intelligent woman, my mother spent her years as a suburban mother—she went back to work very successfully after getting divorced when we were in college, insisting on her twin passions for racial justice and art history. She designed a volunteer-staffed program to bring art history to the elementary schools of a nearby industrial city, because she looked askance at the well-educated women in our leafy suburb who did nothing but play tennis and bridge all day. “They were privileged to have had their educations, and they should be using them,” she said.

As a child, she also scared me witless during the sixties by threatening to go south and join the Freedom Riders, the volunteers who worked with the Civil Rights movement. Ultimately, my father persuaded her to stay home but she drilled her fierce passion for racial justice into our heads the same way she shared her fascination with the cooking of other countries.

Were the dishes inspired by other kitchens authentic? Of course not. In the seventies, she couldn’t get the ingredients in a New England supermarket to make them so, and no one had ever taught her to cook ‘real’ Mexican, Greek—she also made moussaka, or Chinese food. But aside from gustatory variety at the table, these feints at other kitchens were meant to provoke our curiosity and remind us that the world was a vast and culturally rich place beyond the confines of whatever might be found on the shelves at our local Stop & Shop supermarket.

If you’d suggested to that she was being disrespectful of other cultures and food ways with the dishes she made, I know she would have been mortified, because her goal was exactly the opposite. By introducing us to foreign flavors, she was attempting to fight the homogenizing centrifuge of white middle-class American culinary culture, the edible emblem of which is probably Velveeta, the processed orange cheese of no little taste and no provenance.

Curiously, though, she was often skeptical and even a little exasperated when the seeds of culinary curiosity she’d sown in our childhoods bloomed when we became adults. “When did you kids become so fancy and fussy at the table,” she asked once when I brought her some expensive fresh white asparagus from a greengrocer in New York City. The arugula I loved made no sense to her when there was iceberg lettuce to be had, because this cannonball-like green kept longer and could quickly be sliced into wedges and then slicked with bottled salad dressing; Mom drew the line at washing salad greens. And what was the point of a quart of black currant Haagen Dazs when you could get a gallon of Sealtest chocolate ice cream for less money? Her bread habits never evolved past supermarket white in a plastic sleeve, and she had no interest in wine, keeping one gallon of Carlo Rossi red and another of white in her front-hall coat closet for those occasions when her wine-drinking children visited. We joked among ourselves about these bottles of wine as only being a last-resort emergency-landing delivery system and always brought our own wine, knowing enough to pick off the price tag before she went anywhere near the bottle. She remained a convinced customer of supermarket pies and cakes, and was a loyal customer of Saucee shrimp cocktail in pressed-glass tulip-shaped flutes—just pry off the lid and you’re ready to go; Progresso bread crumbs; the canned whipped cream we referred to as Jiffy Lube; and plain old supermarket-brand American baloney.

A suggestion that herbs and spices had best-before dates for a reason, which was that they faded or became acrid, was dismissed as unwanted and unconvincing bad news, and even after the canned vichysoisse made by the Bon Vivant soup company in Newark, New Jersey gave several people botulism, she clung to the cans lurking in the back of her kitchen cabinets (“Bon vivants, no more! My father guffawed the night we heard this news on the radio). Tomato aspic would always be a perfect summer lunch, and the most expedient form of garlic was powdered.

Living alone, her diet regressed to her childhood favorites as she grew older. She actually liked frozen peas and carrots, made omelettes with pennants of American cheese, and renewed her ardor for Gorton’s frozen fish sticks. And yet Mom never stopped surprising me. One of the last dishes she ever cooked for me before moving into an assisted-living home was chicken yassa, a savory West African favorite of chicken cooked with lemons and onions. She’d found the recipe in a magazine, of course, and it was absolutely delicious. “I would so have liked to visit Senegal,” she said when she came back to the table with dessert, Bisquik biscuit shortbread with frozen strawberries. “You know, there’s a huge African imprint on Southern cooking,” she added.

My mother’s gone now, but if she was still alive, I’d insist that she would have been a valuable addition to the test kitchen of any major food magazine. She knew that it was the unselfconscious culinary pastiches of other culture’s kitchens like the ones she cooked for us as children that made us Americans. For many people, these were the essential gateway which induced the culinary curiosity that often led to a sincere desire for more knowledge and authenticity about the foods and cooking of other cultures and countries. And you might want to try her hamburger pizza before you knock it, because with all due respect to the brilliant pizza makers of Naples, it was actually pretty good.