Bistro Paradis | A Tantalizing Taste of Tropical Umami at a Charming New Bistro, B

@Marie Genin

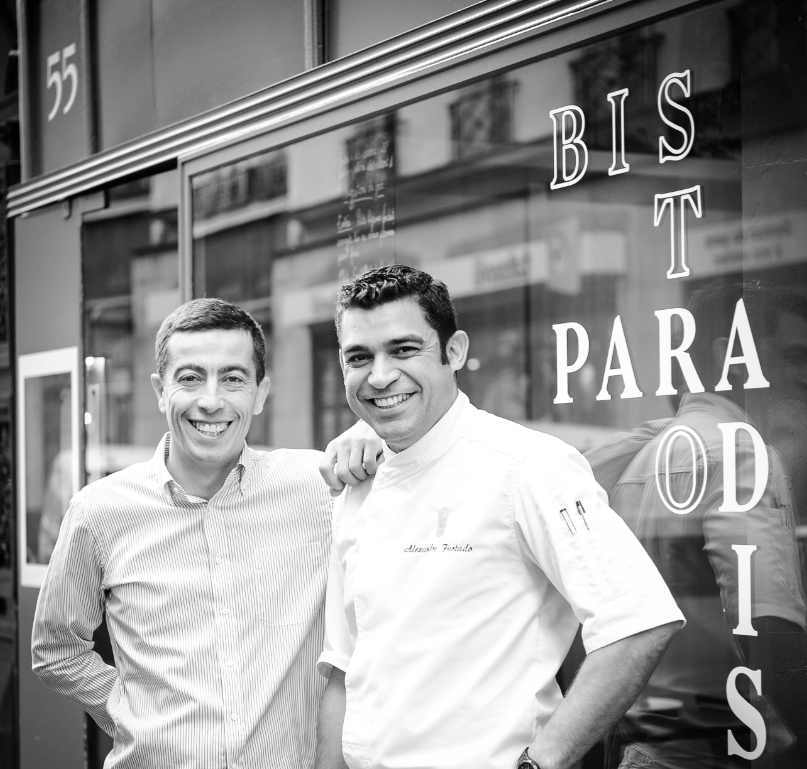

The Bistro Paradis, a winsome new restaurant on the street of the same name, adds some delicious momentum to the ongoing transformation of a formerly fusty part of the 10th Arrondissement into a lively new restaurant district with a lot of adventurous and innovative young chefs. Talented Brazilian born chef Alexander Furtado’s delicious and quietly original riff on the cannon of modern French bistro cuisine also demonstrates how alluringly cosmopolitan this cooking has become in Paris at the beginning of the 21st century. Previously reluctant or resistant when it came to foreign seasonings and ingredients, Parisians have recently embraced them with such wholehearted curiosity that the French capital is quietly becoming almost as wordly at the table as larger cities like New York and London.

Tartare of bass and salmon with lemongrass, ginger and combava @Anabelle Schachmes

“I use typically Brazilian produce like coconut milk and shavings of toasted coconut, guava, mango, acai and pecqui in dishes that are cooked according to the classical French techniques I learned while working at Alain Ducasse’s restaurant at the Hotel Dorchester in London and then at Christian Constant’s restaurants in Paris,” explains the very friendly Furtado. “Contrary to what many people think, Brazilian cooking is characterized by subtle melded flavors, and it’s not hot, which makes it appealing to the French,” says the chef.

What he’s referring to is a flavor palette that might be described as a spectrum of tropical umami, or sweet savoury often nutty flavors which evoke someplace much sunnier than the rue de Paradis, despite a name that would seem to promise an eternity of pleasure. What’s fascinating about Furtado’s cooking is how easily and alluringly the idiom contemporary French bistro cooking embraces his well-groomed expression of childhood taste memories in a huge, distant and famously sensual homeland, Brazil.

@Annabelle Schachmes

In their own way, Furtado and his delightful partner Yoann Dinh are actually perpetuating the traditional vocation of this part of Paris in a different way. For most of the 19th century the fetchingly named rue de Paradis was the honeypot destination where bourgeois mothers and their engaged daughters came to shop for the furnishings that presaged, it was to be fervently hoped, a prosperous life of domestic bliss to come.

Due to its proximity to the Gare de l’Est, the gateway to Paris for trains arriving from eastern France where the best French crystal (Baccarat, Saint Louis) and glassware have historically been produced, the rue de Paradis attracted producer showrooms, and these were eventually joined by shops selling porcelain, silverware and almost everything needed to set an impressively respectable table except for the fresh flowers and the fruit and sweetmeats carefully chosen to ornament the epergne in the center of the table.

During the seventies and eighties, the decline of life-styles that regularly required fish fork and knives, much less silver-plated asparagus clamps or at least three different crystal glasses for each place setting–water, white wine and red, dimmed the glamour once reflected upon the neighborhood by the carriage trade, and by the nineties, the quartier had become filled with African hair-dressing salons, Bosnian butchers, and the kebab stands that are the telltale sign of almost any ‘transitional’ neighborhood in Paris. Now, though, the rue de Paradis is peddling good taste again, but in different declensions, including the handsome interior of bleached oak paneling designed by Kristin Gavoille, an architect who formerly worked with Philipe Starck, that has transformed the narrow premises of a former cafe du quartier into a stylish little room with a lot of personality (it’s efficient, too, since there’s a dumb-waiter at the service bar in the middle of the room that sends dirty dishes down to the scullery below–“This was a challenging space to make into a restaurant,” says Yoann Dinh by way of explanation with a grin).

Meeting Grant, an adored but rarely seen Scottish friend who lived in Paris for fifteen years before he inherited a cottage and pub on a remote island and decided to take a crack at a new life, for dinner, I arrived early and enjoyed a glass of white wine and studying the menu for a few minutes by myself. Just as I found myself vaguely wondering if Grant wouldn’t show up wearing a kilt, someone said, “Hey, how are ya, then, ya old cod!?”

@Annabelle Schachmes

Knowing we’d talk up a storm, I suggested we focus on the food before the chat began. “You know I love living up on my island, but I do miss the luxury of having a huge choice of good food out the door everyday,” said Grant, who was so hungry he suggested we share three starters, the tartare of salmon and sea bass seasoned with lemongrass, ginger and zest of combava, the artichoke veloute with grilled shrimp and chicken-and-lardo-di-Colonnata quenelles (garnishes above before the soup arrived) and the sauté of wild mushrooms with poached egg and shavings of toasted coconut. If all three dishes were beautifully cooked, the detail that stood out for me was the way the coconut shavings brought both contrasting texture and a very subtly sweet mellowness to the wild mushrooms. Grant agreed: “The whole lot is delicious, but I don’t want you start talking food rot with me or it’ll wreck the meal.”

Warned off making my gastronomic observations public, I quietly enjoyed my cod in a lush ‘moqueca’ style sauce. In Brazil, a moqueca is a stew of salt-water fish cooked in coconut milk with tomatoes, onions, garlic, coriander and a little palm oil, and if Frutado’s version was much more refined than the rough-and-ready versions I’ve sampled in beachside restaurants near Recife, it was similarly luscious and deeply satisfying. Meanwhile, grunting Grant across the table was so happy with his marinated steak with manioc fries and a sauce of meat drippings boosted by acai berries (big, healthy fruits that come from Brazilian palm trees) that he got through it before I could exasperate him by trying to photograph the dish. “That was lovely,” he said, warning again, “But that doesn’t mean I want to talk food rot.” Instead he regaled me with the story of his latest affair, this time round with a young Presbyterian minister. “It’s a lot easier to be a poof up in Scotland these days than I thought it would be,” he said.

To be honest, I wasn’t expecting much of the desserts, because most hard-working young chefs don’t have the time or staff to soar at the sweet end of the meal and the ones I’ve had in Brazil were often too sweet for my tastes. So I let Grant go for the banana eclair and settled on some nice ‘pudim,’ or the nice eggy version of creme caramel you find in Brazil and Portugal, with beads of sweet potato marinated in caramel. They were both very good in different ways. The eclair showed off Furtado’s wit and capacity for being a very good student, since there was so much Gallic learning on display in this politely sideways presentation, and the pudim offered up the touchstone of why his food is so good: he has a maternal desire to make people happy and feed them well, and this observation is of course intended as a very big compliment. Or for a more succinct take on the evening from Grant: “Cool operator decor, great grub, sweet young guys–I’d go back.”

Bistro Paradis, 55 rue de Paradis, 10th Arrondissement, Paris, Tel. (33) 07.71.01.32.26 or 0 01.42.26.59.93. Metro: Cadet or Poissoniere. Open from Tuesday through Saturday for lunch and dinner. Lunch menu 23 Euros, Average a la carte 40 Euros. www.bistroparadis.fr