Chez La Vieille, Paris | Daniel Rose Revives the Old Lady’s Bistro, B+

Chez la Vieille has reopened, and this is very good news for anyone who loves the earthy voluptuousness of authentic old-fashioned French bistro cooking as much as I do. We have Chicago born chef Daniel Rose to thank for this welcome and very artful revival, too. Rose is the one who loved this place enough to give it a new life (it’s been closed since 2012), so he staffed it up with talent from his restaurant Spring, just around the corner, including chef Oleg Olexin and Remi Segura, who’s signed the great wine list and runs the two dining rooms.

This has been quite a year for Daniel Rose, too. Hot on the heels of his huge critical and commercial success with Le Coucou, the new French restaurant that I think is the best one in New York City, it looks like he’ll also succeed where so many others have failed by successfully resurrecting one of the most legendary bistros in Paris, Chez la Vieille. Since the original ‘vieille’ (old woman), the famously ornery Adrienne Biasin, hung up her apron and retired over twenty-five years ago, many have tried to keep the fires burning at this snug place once beloved of politicians and show-biz types on a street corner just a couple of blocks the old Les Halles market, which was destroyed in a mad act of municipal vandalism in 1969 when it was transferred to a complex of new buildings tragically out of sight and out of mind of the famously food-loving city in suburban Rungis.

But after Marie-Josee Cervoni, the woman who took over from Biasin when she retired, sold up, everyone who followed in the foot steps of these two ladies failed, including the mercurial chef Michel del Burgo, a flash-in-the-pan eighties wonder boy, and several Japanese chefs, probably because the duplex space is not an easy one to make work, but perhaps most of all because to no one’s surprise without la vieille there was no Chez la Vieille. Several people tried to carry on proposing the lavish hors d’oeuvres course for which this restaurant was famous—herring in cream, celeri remoulade, terrine de campagne, marinated anchovies, grated carrots, potato salad with chunks of cervelas sausage and chopped cornichons, and more, but rather than reading as an offering of maternal abundance as it had in the past, it came off as too much food. It also required too much fussing and fiddling from waiters exasperated by the challenge of circulating these bowls and platters to tables both downstairs and up.

But most of all, the demise of Chez la Vieille signaled that even in Paris life had moved on from the days that anyone could get away with pilfering the whole afternoon necessary to eat and enjoy a meal here. Because when Adrienne Biasin, a.k.a. “la vieille,” was in the kitchen, lunch was a lavish high-cholesterol pageant that ended with the grand finale of a big snifter of Armagnac to celebrate the deliciously anarchic decision to throw all professional responsibilities and personal cares to the winds in favor of a thumpingly good feed that was often followed by a good long nap or maybe some furtive fumbling with someone you weren’t married to in a chilly just-rented hotel room

For my part, I had no idea what I was getting into when a visiting London newspaper editor I occasionally free-lanced for invited me to lunch and asked me to find us a place that served “old-school Cro-Magnon bistro food” and also had a decent wine list. In November 1986, I’d only lived in a Paris for six weeks, so I did some research and finally settled on Chez la Vieille, calling three days ahead of time to book for lunch. I’d never been and was keen to try it.

A gruff-sounding woman answered the phone. I explained that I wanted to book a table for two at 1pm three days forward.

“Mais vous etes qui?” (Who are you?), she asked.

I was dumbfounded. Maybe I’d dialed the wrong number?

“Why should I give you a table? I don’t think I know you….”

“I hope you’ll give me table, Chere Madame, because I’ve been told your cooking is so good, and I’d be grateful for the opportunity to discover it.”

“Are you a politician? You speak like you’re a politician, a lot of shit coming out of your mouth.”

“No, I’m not a politician, I work as an editor in the Paris offices of an American publishing company, and I’ve just moved here from London.”

“Putain qu’on mange mal a Londres!” she said, and I laughed (Oh Fuck do you eat badly in London!). “You’re not English are you?”

“No, “ I told her.

“Okay then, you can come. What’s your name?”

“Alexandre.”

“Okay, see you Friday. Don’t be late, though, or I’ll give your table to someone else,” she said and hung up.

So on a chilly day when I saw Paris nude for the first time—the city’s trees had finally lost all of their leaves, I stepped through the door of this restaurant into warm invisible veils of melted butter and simmering beef, and ran right into a woman with small sharp brown eyes and a prominent nose in a well-worn apron that slouched on her bosom.

She eyeballed me and went for my sartorial jugular, or the much loathed camel’s hair polo coat from B. Altman department store in New York City that my mother had insisted on buying me when I went off to Amherst College in western Massachusetts as a freshman. A more inappropriate garment for that occasion is still hard to imagine, and in fact, the real challenge even today is to divine a situation in which this insanely foppish piece of clothing might have ever been appropriate to the life of a seventeen-year-old boy. It was, however, the only outwear I owned at the time aside from a suede jacket that reeked of sex and cigarettes.

“Alors, c’est quoi ca,” she said, flipping her dish cloth at my coat. “Vous etes un notaire, vous? J’espere que non, car ils baisent mal, tous, ils baisent mal.” (Are you a notary? I hope not, because they’re bad lovers, all of them), she said and chuckled. Oh was she having a good time with me, surely among the most impossibly naïve and wide-eyed creatures who’d ever graced her door. And in retrospect, I can’t say I blamed her, because even though I didn’t realize it immediately, repeated exposure to her painfully accurate teasing made me usefully aware of the tapestry of public vulnerabilities I was displaying in broad daylight following to my recent move to France. To wit, I was self-conscious, often lonely, and wrong-footed by a recurring lack of self confidence. Or in other words, I was rather lost.

Shaking her head, she took my coat, and then she led me by the hand–her grip was firm–into the dining room.

“Who are you having lunch with?” I explained the British editor.

“You’re not having sex with him, are you?”

I blushed and guffawed. “God, no!” She joined in with a cackle and clapped me on the back.

She poured me a glass of wine and came back with a saucer of sliced sausage. She gazed at me for a minute, and then she said, “Why are you so sad when you’re so pretty?” I was spared the torture of finding an answer to that question–I didn’t think of myself as sad, and I certainly didn’t see myself as pretty, when the leonine English editor fumbled his way through the heavy curtains at the door into the dining room. And we ate. And ate. And ate.

First the hors d’oeuvres, then the boeuf aux carottes Adrienne insisted on serving me, and paupiettes for the Anglo editor. I didn’t want beef braised with carrots, because I’m not a big fan of carrots, and I had my eye on the roasted veal, but served with wide-cut homemade noodles, this beef—cheeks and breast, braised in beef bouillon with white wine, carrots, onions, garlic, and a smear of tomato paste was so deeply comforting, it made me teary eyed. Though she loved to preen as a crotchety, even difficult, old lady, this wiry woman cooked with love, and once she’d made up her mind about you, she was fiercely protective and deeply loyal. This was what dawned on me as I ate the beef, which was so tender it cut with a fork, in a sauce that had a tantalizing equilibrium between the sweetness of the onions and carrots and the acidity of the tomato and wine. The editor loved his paupiettes—veal cutlets stuffed with forcemeat and tied into lard-barded bundles with fine string—in Port sauce with baby vegetables, too. Adrienne’s crème caramel was the best I’ve ever eaten until very recently at La Bourse et La Vie, which is also owned by Daniel Rose, and bien sur the meal ended with Armagnac, and, rather horrifyingly, some tears.

The London editor had recently founded out that his wife was having an affair with the builder hired to do some work on their house in Hampstead. And when he’d challenged her about it, she’d told him she was leaving him for the new man who was handy with a hammer. Awkwardly, I tried to console him, and was only delivered when he glanced at his watch and realized he had to rush out the door to get his train at the Gare du Nord. So he flung two five-hundred-franc notes on the table and was gone.

Adrienne told me that she didn’t have the right notes to give me change for bill, which was somewhere around 675 francs. So I told her to keep the money on account as a credit for my next meal there, an idea that pleased us both a lot. I went back a week later and spent the remaining 325 francs and more. And this became a happy Friday habit.

So I wondered what to expect on my way to Chez la Vieille the other night. How retro would Rose go in resurrecting this restaurant? And actually, how retro did I want him to go?

On the one hand, memory has anointed Adrienne Biasin’s cooking with gold leaf, but walking down the avenue de l’Opera on a cool night, I couldn’t help but daring myself to admit that sometimes her cooking could be a little bit, well, a little bit bland. And as much as I loved her, I never loved the dining rooms—the big bar downstairs took up too much room, upstairs felt like right field, and the lighting was terrible in both rooms.

Well, first things first. Interior architect Elliott Barnes new look for the restaurant is pretty brilliant.

Barnes has retained with the white-gray-and-black tiles of the downstairs dining room, but cleared out the tables downstairs in favor of a handsome new bar made from tin and light wood with a rank of bar stools where you can sit for a drink or a meal. Upstairs, reached as always via the stairwell of this 16th century house, the high ceilinged dining room with only eighteen covers has been painted tea blue and kitted out with banquette seating along one wall, modern sconces designed by Barnes, and a chain-mail chandelier overhead that struck me as incongruous in this setting.

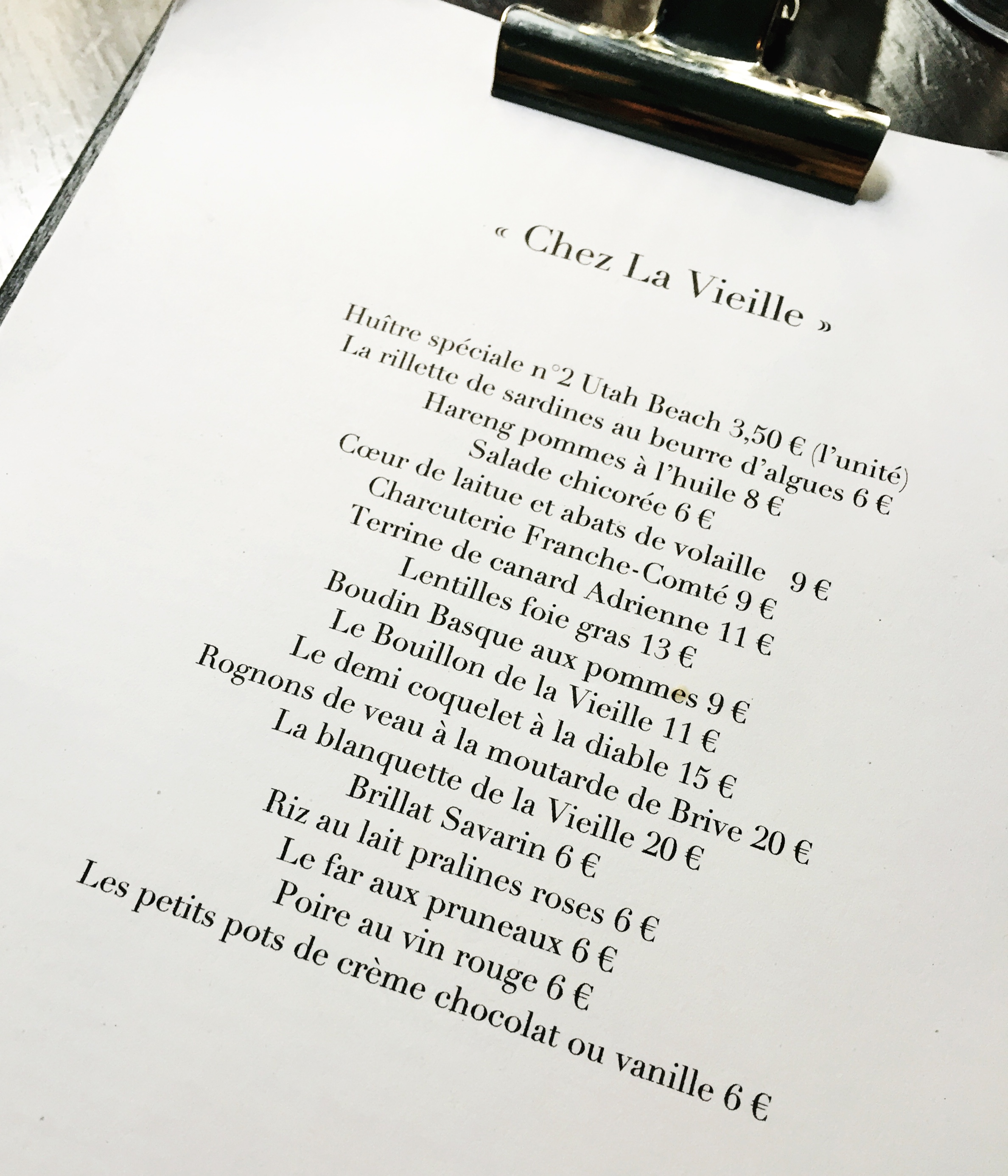

Helmed by chef Oleg Olexin, the menu is intelligently concise but very appealing. Dismissing options like the Utah Beach oysters from Normandy, the sardine rillettes with seaweed butter, and the bibb lettuce salad with chicken gizzards, we ordered starters that seemed more likely to honor the late Madame Biasin and also show off the kitchen’s talent.

And indeed the unctuous duck terrine ‘Adrienne’ shot me back through time in the most ruthless of ways, since this soft but firm slab of minced duck meat, organs and fat has the kind of low-ball barnyard funk that Madame Biasin always made her signature. Here the terrine comes with a racy beet-juice red grated horseradish condiment and onion jam; both are excellent. Bruno’s Puy lentils with two soft slabs of foie gras were a sexy upstairs-downstairs pair, too—two perfect products that flattered each other in a horny rural coupling.

When it came to ordering mains, we side-stepped the highly recommended coquelet a la diable, knowing that we’ll eat here again soon, in favor of two dishes I perceived as urgently expressing both Rose and Biasin—bouillon with spaetzle, grilled bacon and a poached egg and blanquette de veau, which in English rather insipidly translates as veal in cream sauce but is in reality just so much more than that. Done well, which is a real art, this dish of tender meat with baby onions, the occasional carrot, and miniscule button mushrooms is just about as comforting as being swaddled in white flannel sheets, put in a cradle and rocked in front of a wood fire by your grandmother on a rainy night. Rose is also rightly obsessed by the restorative qualities and pleasures of an honest long-simmered bouillon, and the one served here stands out as the single best comfort food to be found anywhere in Paris this winter.

What makes it even more interesting is that it’s a dish that Adrienne Biasin would probably never have served, since for her it would have felt unfinished. She would have wanted to whip the egg into the sauce rather than leave it whole, for example, and might have been puzzled by the grilled bacon as well, not knowing, of course, that bacon and eggs is one of the most essential and primal comfort-food pairings in the entire English-speaking world. But this deeply restorative dish, a preparation as restaurant (the old French word for ‘restorative,’ and yes, the genesis of the modern word for a public place to eat, since the original ones in Paris served variously garnished bouillons) as any hundred patented modern medicines, displays Rose’s profound knowledge of French cooking and its history, and also the nimble outsider’s irreverence that allows him to tinker with a cuisine he has succeeded at making his own.

Remi Segura’s off-list Domaine Ganevat Chamois du Paradis Cotes du Jura was a superb suggestion for this meal, and his service was all easygoing charm throughout a meal which I’d criticize in only two places. The garnish of Basmatic rice with toasted almonds and snipped apricot to be eaten with the blanquette de veau came in a tiny dish and was awkward to eat from. When I mentioned this, I was told that I should have dumped the rice into the cast-iron Staub casserole the blanquette de veau came in and eaten out that directly. This would have been complicated in a variety of different ways, since it would take forever for the whole dish to cool off enough to eat, it would be complicated to try and cut chunks of meat in sauce in a high-sided casserole, and the deliciously crunchy almond chips would lose their role if soaked in sauce. So better in my opinion to serve the rice in a larger side dish so that the pleasure of the blanquette can be parsed out.

Given the generous portions here and the heartiness of the cooking, we decided to split a portion of rice pudding with crushed praline rose (almonds in a pink-colored hard candy sugar shell, a popular comestible in Lyon) at the end of the meal. For me it was too sweet and too mushy, and I’d have liked a little bit of crunch from freshly crushed pralines to contrast with the soft, creamy rice. These are quibbles, however, since Chez la Vieille is not only an excellent restaurant but quite possibly a better one than it was under the aegis of the late Adrienne Biasin, who would doubtless also be glad to know that I gave my much loathed camel’s hair coat to a clothing bank a good twenty-five years ago and that I’ve never ever had sex with a notary.

1 Rue Bailleul, 1st Arrondissement, Paris, Tel. (33) 01-42-60-15-78. Metro: Louvre. Open Tuesday through Saturday for lunch and dinner. Closed Sunday and Monday. Average 45 Euros.