Divellec, Paris | High Tide at Les Invalides, or a Brilliant New Fish House, A-

@Romain Laprade

The Divellec is one of the most beautiful new restaurants to open in Paris for a very longtime. As wonderfully louche as Studio K.O.’s Miami-meets-1940s Casablanca-in-Paris decor may be, however, what always matters most to me at a restaurant is the food, which is superb. Still, even though the seafood cooking at this venerable old-school fish house overlooking the Esplanade des Invalides on the Left Bank has been brilliantly rebooted by young chef Matthieu Pacaud, the son of Bernard Pacaud of the three star L’Ambroise on the Place des Vosges, this reopening has gone oddly under-remarked in a city as food-loving and mad for fish as Paris.

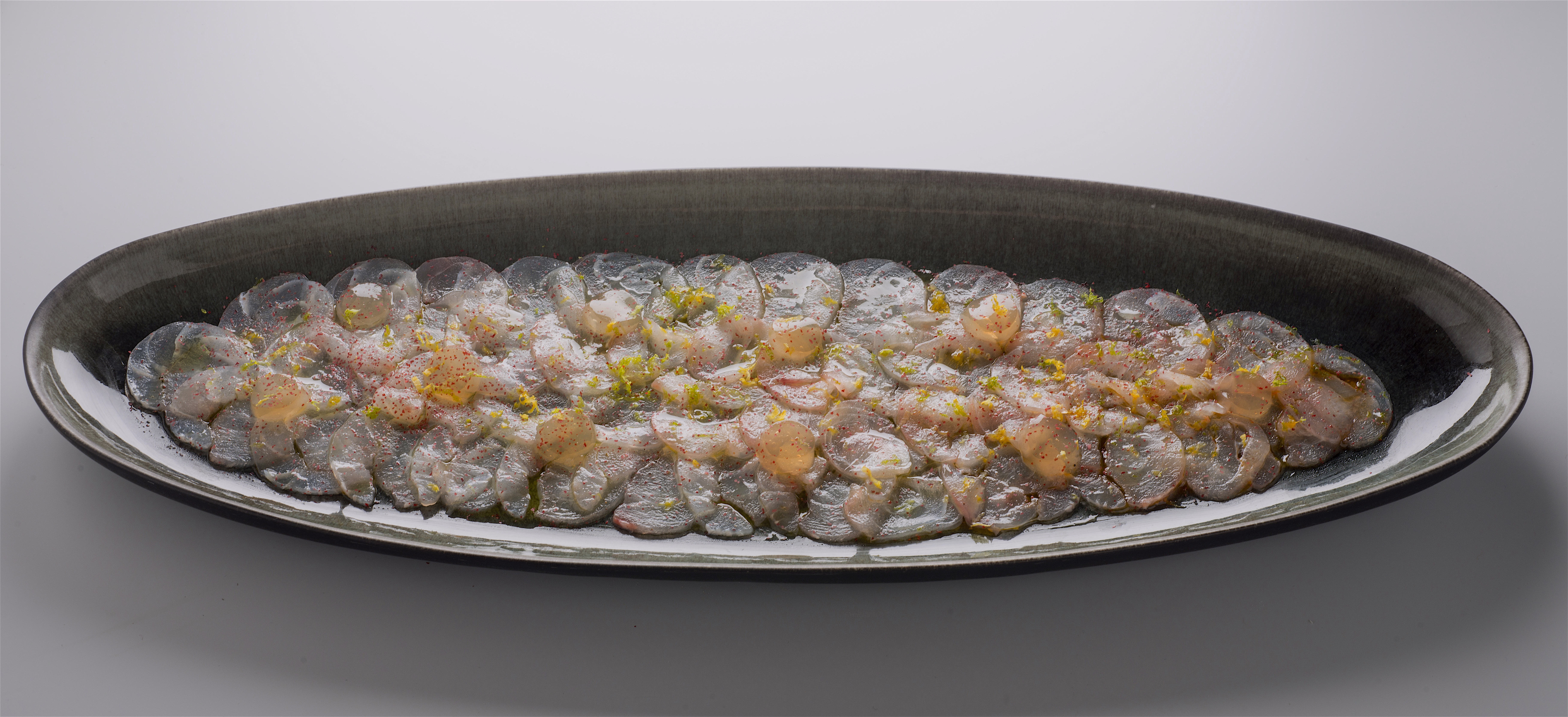

Sea bass carpaccio with citrus zest@Jacques Gavard

There are several reasons for this. First, the public relations firm charged with the relaunch emphasized the revived restaurant’s decor over its kitchen. This is doubtless because the chic Paris based Studio K.O. firm, which did the interiors of madly popular Chiltern Firehouse hotel and restaurant in London, also signed the new look for Divellec, too. But unless you’re enough of an interior-design nut to know who Studio K.O. is, it’s hard to see why any restaurant would emphasise its decor–gorgeous though it may be, over its food.

Then the restaurant had also been closed for three years after founder Jacques Le Divellec retired in 2013, so it fell off of a lot of people’s radars, and then those who remembered it, probably had an idea of a place that was slightly stuffy, somnolent and very expensive. Finally, Divellec is located in a very quiet, wealthy, well-guarded, older part of Paris, so it was unlikely to immediately gain much traction with the city’s best young food writers, those types who’d rather go belly to the bar at Clamato.

@Yann Deret

So with all of this in mind on a cold misty Sunday night as Bruno and I walked to dinner here for the first time since the reboot in a companionable silence, my expectations were vague. The truth, you see, is that I’d never actually had a meal at the former Le Divellec, a fusty bastion of politicians and captains of industry at noon, and the same in the evening with their mistresses, that I’d actually enjoyed. To be sure, I had once eaten a sublime grilled lobster a l’Amoricaine here with a stunning bottle of Mersault as the guest of an Irish banker whose freckled cherubic face existed as the perfect foil to his psycho-sexual perversion. But my last meal here, oh at least a good ten years before the lights went out in 2013, was my most memorable, since I had been invited to lunch by one of the most powerful and un-repentently honest food critics in France.

What I remember was the soft stale fishy smell of the dining room, the witheringly haughty service, and an awful lot of bland white sauce lashed all over everything. “How would you describe this meal, Alec?” the esteemed critic asked me. “Hotel du Lac,” I replied. He looked blank. “That’s the title of the British novelist Anita Brookner’s novel about a lonely middle-aged single woman who goes on holiday to a sad, sedate, anonymous, expensive hotel on a Swiss lake. She takes all of her meals in the hotel, and even though few of them are described, I imagine that they’d have been like this, soulless under-seasoned over-cooked luxury cooking,” I explained.

No one recognised the critic until after our very disappointing main courses were being cleared away. Then a silent thunder bolt shoot through the room, and a frantic Commedia dell’Arte like performance began when we were served an insanely generous portion of Beluga caviar with shocking speed.

@Romain Laprade

“Oh Mon Dieu,” the critic sighed when the glistening black fish eggs were brought to the table with blinis. “Please….,” he said, waving his hands. “We’ve finished our meal already.” The face of the older waiter who’d just served us was a rigid mask of fear. “I think this might be the best dessert ever invented,” he said, a great line delivered with a poignantly plaintive smile–he was, after all, the solider on the front lines. The half beat of silence encouraged him. “It would be a shame to waste it now,” he said, his body locked in a half-bow. Silence. More silence. A short negative head shake. Several hundred Euros of caviar departed to an uncertain fate, and the scene stirred a ripple in the dining room, a place I always thought of as a theater of unwanted kisses, since the people who paid the bills here were usually avaricious, physically or psychologically, with their guests. You know, the lupine old man with his mistress, the curmudgeonly grandmother making menacing remarks to her grandchildren about the uncertainty of their inheritances, the broken middle-aged couples on the edge of a divorce caused by an infidelity they didn’t have the spleen left to discuss.

This is how restaurants get a reputation in our collective consciousness, with some being tagged as warm and happy, others cold and melancholy. So even if Le Divellec of yore was a storied table that once had a Michelin star, maybe two, and served reliably fresh classically prepared seafood, I think I’d be hard put to find very many Parisians who remember actually having had a good time here. So as we reached the front door, I found myself hoping this curse might have been lifted.

Fair’s fair. Sunday night is not an optimum time to judge any restaurant more ambitious than a brasserie, so as we were seated in a pretty grass-cloth upholstered room with low lighting and lots of plants, I thought, well, what I’m hoping for is just a good meal, not a revelation.

Scallop carpaccio with caviar @ Jacques Gavard

You see the old Le Divellec kind of missed the boat when it came to a sea change in fish cookery that was launched in Paris at the beginning of the 1980s by Gerard Allemandou at La Cagouille and the Minchelli brothers at Le Duc, both in Montparnasse. What they espoused was a bracing just-plucked-out-of-the-sea minimalism that was more Japanese in approach and theory than French.

The self-taught Minchelli, a native of Marseille who now runs Le 21, a confidential and very good little fish house in Saint-Germain-des-Pres, cast off the robes of Escoffier–his sauces, and served fish almost naked. He invented this dead simple approach to seafood cookery while running his first restaurant, Le Duc, on the Ile de Re, which he later moved to Montparnasse. Long before anyone understood fish would soon become a luxury food, Minchelli was cooking it in such a way as to enhance its natural taste and texture, his reasoning being that it was so good as nature made it that it needed almost nothing more.

Some twenty-five years later, Minchelli’s approach, now adopted by most other Parisian chefs, exhibits its dazzling prescience more strongly than ever. But Pacaud picks up where Minchelli left off is with a new sense of gastronomic wit and puckish aesthetics that this now vintage school of seafood minimalism had been wanting. To wit, yes, we know we should be eating species of fish that are not threatened with extinction, mackerel instead of cod, for example. Yes, we know we should eat lighter, cleaner and less. But on the other hand, even if these lessons have rightly become so integrated into the culinary behavior of modern Paris, it’s still an occasional pleasure to veer off course, or to chose pleasure as a direction over any other point on the compass. So the challenge is to create contemporary fish dishes that don’t mask the natural flavor of the fish but are also inventive, festive, attractive and even a little bit amusing.

This is what I thought while an array of very pleasant hors d’oeuvres began our meal–an oyster napped with peppery watercress sauce and dabbed with herring eggs, a single butter-roasted scallop with a coin of fragrant black truffle and a wood-sorrel corsage. This succession of little dishes did exactly what good hors d’oeuvres always do, which is to offer teasing glimpses of the kitchen’s gastronomic garter belt to excite expectations for the meal to come.

The menu was totally tantalizing, too, especially since I’d decided to play the old what-the-hell card, too. By this I mean, that in today’s world everyone I know is so desperately over-worked to such a degree they rarely take the time to spontaneously enjoy themselves. You know, to just say, ‘Okay, screw it. I’m turning off my phone and my computer until Monday, and I’m just going to have a good time without planning it in advance. We work like dogs, we’re not machines, and if we don’t anoint ourselves with the occasional extravagance, what’s the point of the whole thing, i.e., a career?” Bruno looked a bit wan when I suggested we just go ahead and enjoy ourselves, because aside from some reasonably priced prix-fixe menus, the a la carte tarifs are pretty stiff.

I was extremely tempted by the tuna-and-dried-fruit pastilla with a coriander and ‘virgin’ celery reduction to start, but finally settled on ecrevisses, meaty little crayfish from Alpine lakes that are rarely seen on Paris menus, with a passionfruit vinaigrette and a cauliflower ‘zephir’ (sort of a soft custard of the same vegetable) at 65 Euros, while Bruno couldn’t resist the sea bass carpaccio with green apple gelee, crushed mixed peppercorns and citrus zest (38 Euros).

If the sea bass carpaccio was exquisite, my crayfish were too timidly seasoned and the cauliflower cream reminded me more of the old Le Divillec than the new one (and in case you were wondering, yes, it lost its article, ‘Le’ in the reboot and is now known just as Divellec) and was also a bit stodgy eighties vintage Robuchon in logic. Maybe the dish would have worked better if the passionfruit vinaigrette was more vivid, since it was nearly undetectable. That said, the crayfish were succulent, sweet and perfectly cooked.

The wine the natty sommelier suggested, a Romorantin from the upper Loire, was as perfect with his meal as his nimble commentary on the bottle. Without being showy, he mentioned that it had been one of the French king Charles V’s favorite wines and that the region was one of the extremely rare ones in France that had not been devastated by phylloxera in the 19th century, so the ancient root stock of the vines that produced the grapes from the wine was made is as powerful an expression of an intriguing and little known French terroir as one could hope for. Formal though he was, he was a very nice man who allowed as how he’d worked in California for many years and had recently returned to France, too.

The Sunday night tables around us were obviously having a good time, too. The stunningly good-looking just out of bed couple where the gent was clearly terrified of racking up too large a bill, the middle-aged couple who discussed almost every forkful of what they ate with the delightful young maitre d’hotel in a ritual that rippled back to paper road maps and the Michelin red guide on the dashboard, and an Italian mother and daughter from Milano who were insane for the decor and loved the food, too.

Following my crayfish, sole with grilled walnut butter and braised salsify with black truffle was magnificent. The distant sweetness of the nut loved the pearly flesh of the fish and the salsify provided textural contrast with the sole and softly punched its iodine with an earthy gust of truffle. Bruno’s John Dory with steamed shellfish–cockles, mussels, tiny shrimp, in sorrel cream was equally elegant.

Though I wouldn’t have wanted it, a cheese trolley should be proposed at a restaurant du plaisir like this one instead of just an assortment of four already plated cheeses from the admittedly excellent Quatrehommes cheese shop in the rue de Sevres where I whiled away many happy half hours back in the blessedly long-gone days when I used a laundromat just around the corner. So since we were well fed and happy, we decidedly to split a freshly baked individual apple tart with caramel ice cream, and it was lovely.

So here’s what I want next time round: line-fished sea bass cooked in a sea-salt crust and served with a citrus sabayon. But since this flops on the deck at 15 Euros for 100 grams of fish, what I can honestly look forward to the next time I visit Divellec is brunch, which may surprise all of the friends I have who know that I normally loathe this meal (Why? The gustatory rewards of being dressed and in a restaurant during brunch serving hours on a weekend are almost unfailingly never worth it, and it’s the worst value for money meal in Paris most of the time, since plain old eggs get kicked upstairs by a factor of ten, sometimes twenty, on what they actually cost).

But if dinner was excellent, the brunch menu really speaks to me:

Fresh juice

Hot drink

Selection of bread and pastries

Butter and organic jam

Botarga bruschetta

Perfect egg Florentine

Bass ceviche, lemon juice and pink berries

Scallop burger, fresh herbs

Thin apple pie with toffee ice cream

or

Soufflé of chocolate grand cru, Bourbon vanilla ice cream (extra 10€)

49 €

with a glass of Champagne Thienot 65€

So what do you think? Meet me there?

Divellec, 18 rue Fabert, 7th Arrondissement, Tel. (33) 01-45-51-91-96, Metro: Invalides. Lunch menu 49 Euros, Initiation menu (four courses served at both lunch and dinner) 90 Euros, Tasting menu – eight courses, served at lunch and dinner. Brunch menu 49 Euros. Average a la carte meal 110 Euros. Open daily for lunch and dinner. N.B. You can make reservations via their website, too: www.divellec-paris.fr