Lucas Carton | The Rejuvenation of a Mythic Parisian Table, A-

They’re few dining rooms in Paris that are so deeply invested with a long and mostly very happy album of memories for me than Lucas Carton, the magnificent landmarked restaurant with a spectacular art-nouveau decor by Louis Majorelle just across the street from the Église de la Madeleine in the heart of the city.

So I was a little anxious when I went to dinner here the other night for the first time in a very long time–my purse doesn’t allow me to be a regular, and ultimately relieved but not surprised to rediscover that young chef Julien Dumas’s cooking makes him a brilliantly worthy successor to Alain Senderens, who had billing as head chef here for almost thirty years, despite the fact that it was his lieutenant Jerome Bactel who’d actually been running the kitchen on a daily basis for a while.

In fact Bruno said that our meal reminded him of his initial experience of Yannick Alleno’s cooking, or a dazzling first encounter with a startlingly talented and rapidly rising young chef, and I quite happily agreed. Dumas is exactly what Lucas Carton needs to remain a relevant and desirable restaurant in Paris in 2015. So ultimately I was able to add another gastronomic sketch to the brief but privileged album I carry around in my head of occasions spent on these premises.

To be perfectly honest, the one that really sticks out in this slender volume of memory is deeply tinted to this day by trauma. When I arrived in Paris from London to work as an editor in the rue Cambon offices of Fairchild Publications, this restaurant was the setting for one of the most excruciating meals I’ve ever had in my entire life. Sifting through the still tender shards of remembrance attached to that evening, I don’t find the name of my host or hostess, but I know it was a Paris fashion designer and that the chic little supper was intended to size me up and ‘welcome’ me to Paris, in that order of importance.

To say that things did not go well that night is a massive understatement. My eight years of French failed me miserably within minutes of being seated between the attache de presse who’d organized the evening and a druggy middle-aged Countess who immediately told that she thought les Americains were “des sauvages” (savages) and who regularly left the table for five minutes or longer to then return with white-powder-rimed nostrils. In retrospect, the least she could have done in those days before I became sensible and settled was to offer to share her loot. In any event, the meal was a horror, and the worst of it was a starter salad, a tumble of pretty little leaves, that looked innocent enough until I noticed a tiny gnarled bird’s leg sticking out of the greenery. This leg was so tiny I couldn’t imagine anyone would actually want to eat it, and I found myself wondering if it might have found its way into my plate by dint of some horrific accident in the kitchen, or maybe it was a practical joke, or maybe….

It was the druggy Countess who see me straight by making me the object of shrieking hilarity for the rest of the meal. “Eeets a delicacy, Alexandre! Un grive, a leeetle wild bird with a good funky taste!” Oh, of course. A good funky taste, well now we’re talkin’. Eh bien sur, I used to see packets of grives all the time at the A & P in Westport, Connecticut when I was a child. Not. So I gnawed on the little nugget of meat on the tortured avian leg, and it to my surprise it was fleetingly delicious, because, well, it had a good funky taste.

Over two decades later, I’m still astonished by the fact that the eleven other people at this table not only did nothing to put me at ease or get to know me better, but actively enjoyed my discomfort and repeatedly maladroit manoeuvres. Walking home, I couldn’t help but thinking of one of my mother’s well-worn anecdotes, which was about a boyfriend from Kansas who accompanied her to a clam bake on the North Shore of Boston one summer night, and after being served his lobster before everyone else, he attempted to open it with a knife and fork like a piece of meat, and, frustrated, said, “This is the toughest lobster I’ve ever eaten.” Everyone else agreed heartily, and then encouraged him to pull the beast apart and crack it up with the lobster-claw-shaped aluminum pincers posed on his napkin. “I only put them out when I know the lobster’s going to be tough,” explained the hostess.

What’s nice today, then, is that Lucas Carton no longer intimidates me. In fact, there’s almost no place left in France that does, since I’d dare to say that I’ve long since cracked the codes of Gallic luxury so thoroughly I’ve actually come full circle and recovered my original innate New England preference for simplicity, which never fails in the kitchen or any other realm of life as far as I’m concerned.

Happily, Julien Dumas, who worked with both Alain Ducasse and Jean-Francois Piege, but whose true gastronomic maitre is Jacques Maximin, one of my favorite French chefs, both for his cooking and his personality, is another acolyte of the late great French food critic Maurice Curnonsky’s dictum that ‘Great cooking is when things taste of what they are.” I first tasted his cooking when he was working at Rech, Alain Ducasse’s seafood brasserie in the 17th Arrondissement, and I was immediately impressed by the delicious gastronomic symmetry of his impressively lucid style.

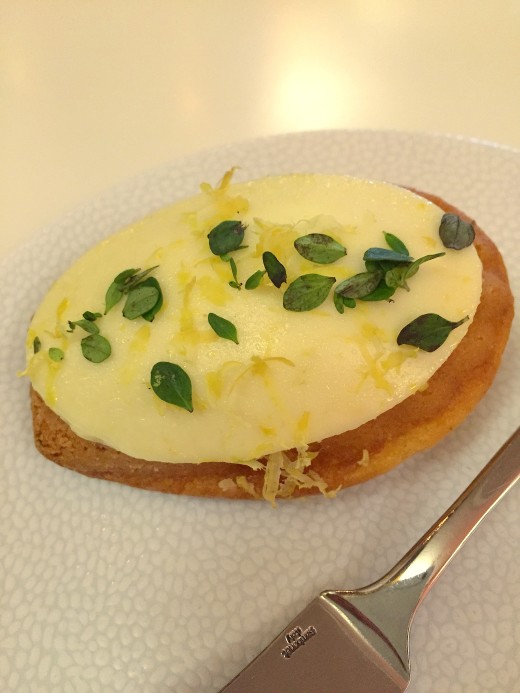

Much too often the pretentiously named amuse bouches (amuse the mouth, a fancy name for the similarly fancily named hors d’oeuvres) that begin a meal come off more as a fiddly waste of calories than anything that actually provokes pleasure. But not at Lucas Carton, where they do exactly what they’re supposed to do, flirtatiously excite your interest in the meal to come. Dumas’s Parmesan madeleine with citrus rind and deliciously acidulated puree of ‘chou pointu,’ or tender turban-like Pontoise cabbage that’s at its best in the Spring. with match-stick slices of dried mullet were racy little pleasures that couldn’t be dampened even by the rather sullen waitress who brought them to the table.

After a composition of morels and shaved squid that was such a brilliant terre-et-mer (earth-and-sea) pairing that I disregarded my reportorial duties in favor of pleasure, the next course was a luscious lobe of roasted beet-juice lacquered foie gras with roasted beets, beet greens and potato puree. Recourse to the superlative is slippery ice by definition, so I’ll moderate myself and say that I think this was the best foie gras I’ve ever eaten, with a dusting of herbs that included rosemary, plus Maldon salt, and the texture of just set custard.

I hadn’t been to Lucas Carton in such a longtime that I’ve forgotten about the way that meals here are rather insistently trellised to the idea of serving a glass of wine with every dish. I’m not a huge fan of this idea, since I find hoping from on overwhelms the palate and gizzards. That said, the Reisling Kabinett 2007 Piesporter Goldtropfchen Riechsgraf von Kesselstatt from the Moselle in Germany napped the foie gras perfectly by reprising the distant sugar in the beet garnish.

This last remark makes the meal sound awfully serious, and alas, it was, which runs contrary to the reason that most people decide to treat themselves to an expensive meal, which is in the hope of gastronomically amplified pleasure. Unfortunately, French haute cuisine has developed an encrusted, rigid and rather joyless service style that often wilts high spirits instead of teasing them. But hopefully over time the urgency of Dumas’s brilliant cooking will induce a psychic or sociological change in the stiff posturing of the dining room staff.

Dumas is one of the best fish cooks in France, so I was especially curious about the next dish, Whiting with buckwheat. The perfectly cooked filet came encased in a crispy buttery buckwheat crepe in a pool of sauce that tasted like a pil-pil sauce with the addition of buckwheat. It was an elegant and deeply satisfying dish.

Roasted pigeon with a sauce of Sicilian pistachios from Bronte was an inspired idea, too, and Dumas’s perfectly crusted sweetbreads in an sauce of carrot juice and veal stock gentled spiked by mustard seeds marinated in verjus was lusciously earthy.

The La Spinetta Moscato d’Asti served with a dessert of Mara strawberries garnished with jasmine petals, caille, yogurt ice cream and buttery caramelized wafers was a brilliant pairing, too.

Ultimately, this was an excellent meal, which made me eager to go back and try the more affordable menu du march served in the more relaxed dining room upstairs and also the relatively good value lunch menus served in the Majorelle dining room at noon. And since Lucas Carton is now back on my list of special occasion tables both for myself and for anyone who asks, here’s hoping they’ll also soon bite the bullet and remove all and any trace of Senderens wildly ill-considered interior-design attempt to turn one of the world’s most beautiful dining rooms into something trendy. Cooking as good as Dumas’s warrants the head-on beauty of the original room.

9 Place de la Madeleine, 8th Arrondissement, Paris, Tel. (33) 01-42-65-22-90. Metro: Madeleine. www.lucascarton.com Menu du Cercle (lunch): 89 et 99 euros. Tasting menu: 179 euros. Average a la Carte: 150 euros. Brasserie le Marché de Lucas (casual dining on the first floor): 45 euros (lunch) et 52 euros (dinner). Closed on Sunday and Monday.